I’M GOING TO GRAD SCHOOL

I’m trying to tell you something ‘bout my life

—Indigo Girls, “Closer To Fine”

Six years ago, I was on a trip across the Midwest with my then-girlfriend, on our way to Nebraska. We first stopped in Chicago not just because I’d never been and it made sense with our timeline, but also because I had an appointment to meet with a professor of musicology at Northwestern University. In 2017, I thought I wanted to be a musicologist, and this professor had made quite a name for himself writing about Morton Feldman, a composer whose work has been central to my own development as a composer and thinker-abouter of music. A few weeks before that meeting, I’d lost my voice in a bout with asthmatic bronchitis, and I was nervous that I wasn’t going to make a good impression. As it turns out, it wasn’t my voice that was to blame for what I felt was the lukewarm reception. It was the fact that I no business applying to a musicology department at all, and, having been out of school for 6 years at that point, I was not prepared for a conversation with one of the most prominent musicologists in the country. Still, I applied to Northwestern’s program (after having written a 55-page study about trends late 2000s rap music), and was, no surprise, rejected.

Kendrick Lamar’s DAMN. tour in Lincoln, NE, August 2017

It wasn’t so much that I wanted to be a musicologist, it was that I saw someone interested in many of the same things I was in a position at a university and figured that that must be the way forward. I was, by my standards, a failed music student. I transferred out of the music conservatory at SUNY Purchase after two years in their composition department because I was completely depressed and dissatisfied with the program and my lack of a social life. I finished my undergrad at SUNY Albany, and while that program may not have been what I needed, my social life had picked up, as did my performing career, now back in my hometown with all the connections I’d made before leaving for Purchase still intact. (It didn’t help that in 2017 I was dating someone who was simultaneously getting her JD and PhD at Cornell. Talk about imposter syndrome.) I knew I had more inside me, not as a musicologist, but as a composer (I should never have abandoned that in the first place), and I spent the next 5 years, off and on, applying to schools: 2018, 2020, and 2022. After the 2018 and 2020 rejections, I told myself: never again. I’m not one to take rejection well in the first place. But, having an oversized confidence in my abilities as a composer, these rejections were particularly difficult to accept. (I should say that through 2020, I was stupidly applying to PhD programs which, because of my not having a masters, I was almost certain to be rejected from on principle.) It was only in 2020 that I got my first interview, and they seemed to like my work and invited me to sit in on some classes and meet with faculty (on Zoom, of course; this was the height of the pandemic after all). They still rejected me. My one and only interview, and it was not to be.

***

My senior year of high school, a friend gifted me a VHS box set called “4 American Composers”. I could not have predicted at the time what a profound impact these hour-long documentaries on John Cage, Philip Glass, Meredith Monk, and Robert Ashley would have on my career. I watched them incessantly. Not the Robert Ashley one, though. I didn’t like his music. I didn’t get it. It was just talking. And who wants to hear about the Corn Belt for 3 hours? But the other three…ohhhhh man, those videos would set me up for the next 14 years of musical exploration (right up through 2021). I was writing all sorts of indeterminate music, minimalist music, and vocal music, all further inspired by composers like Earle Brown and Morton Feldman and Charles Ives. Of course, I was writing all this music (some 300+ compositions) without any hope of it being performed (since I had left Purchase and all). I was just writing to write because, naïvely, I thought that one day I’d be discovered and given the opportunity to show the world what it had been missing. And when that time came, I had to be ready with my best work. I chalk this attitude up to typical teenage and early-twenties narcissism. Oh, and the various mental health crises I’d had over the years. Happy to report now that that’s changed. What did not change, thankfully, was my core belief that I was a great composer and that I had something unique (which is different from important) to say. What had not left me in all those years was—during a Q&A with the composer at SUNY Buffalo in 2007—what Philip Glass said to me after I’d asked him what I should say to people who think my music is too weird (I’m paraphrasing here): Ignore them, you just have to keep writing. And maybe that’s what buoyed me through all the grad school rejections. If I’d had the good sense to believe that it was my rather lengthy break from academia (plus my hubris in applying to doctoral programs) that kept me out of grad school, I might have actually felt like there was no recovery from that. Feeling like an outcast, however, was not new to me; I wore that badge proudly, and that I knew how I deal with.

***

In my time at SUNY Albany, I took two classes with Dr. Nancy Newman. (Associate Professor Nancy Newman specializes in European and American musical practices since 1800, with an emphasis on the relationship between art, music, and popular culture. Her interests include critical theory, film music, and feminism—www.albany.edu.) Those classes, Representations and Music Since 1900, combined what one might think of as traditional music and art history curricula with lessons about gender, sexuality, race, and cultural critique, always including thoughtful group discussion (or as thoughtful and energetic as you can expect from undergrads in the late-afternoon). This interdisciplinary approach really appealed to me, as I was thinking a lot about theatre, visual arts, and capital-c Culture at the time, and also how my own work fit into the larger scope of music history, particularly which dead composers’ torches I was picking up in my compositions. I would go on to write final papers about a multi-dimensional approach to time in Cage’s Concert for Piano and Orchestra and gender representation in Sondheim’s Company. Dr. Newman really pushed me to think about how my own identity informs my compositions and general approach to music-making. She was one of the first people I met who seemed to know a little bit about everything, which was, and still is, the kind of person I want to be.

After I graduated from UA, Nancy came to see me perform quite a few times with my then-band, Filming Ohio, and as a solo artist, memorably at my Jack & Jill EP/Short Film release concert (which features a fully nude Justin Friello toward the end of the film, something my mother would later describe as “very forward”) and my show at WAMC’s The Linda. She commissioned two works from me, an arrangement and recording of an anti-rent political campaign song from the mid-19th century and a contemporary reworking of that melody as an anti-Trump piece. This past October, she invited me to give a special lecture in that Music Since 1900 class which I called, “What Is Style? Stephen Sondheim and Pop-Music Mashups”. Nancy deeply understands what I’m about. She remembered the Sondheim paper from 11 years earlier. And all this time she’s trusted me enough to bring each of these projects to life, even when they’ve been unlike anything I’ve done before. To say she’s been supportive is an understatement, and it should be no surprise that she’s written a letter of recommendation for me every time I’ve applied to grad school without question, without ever asking if I’m sure this is what I want to do (even when I’ve asked that of myself). Just two weeks ago she wrote me an email to say, “I think you’re going to thrive in grad school.”

Slide #5 from “What Is Style? Stephen Sondheim and Pop-Music Mashups”

***

In 2014, I moved back to Schenectady from New York City, nearly broke, having, after a 4-year relationship, split from the girlfriend I met at UAlbany (we’ll call her Girlfriend #1; JD/PhD is #2). One of the first people to reach out to me after the move was Charlie Owens, a friend (now, one of my best friends) I’d been introduced to at UA through #1. He was now Company Manager at Capital Repertory Theatre in Albany, and he let me know that they were looking for actor-musicians for a new production of The Secret Garden. Now, I had no formal theatre training. I did lots of acting in high school (we were lucky: 4-5 shows a year, lots of funding), and I did a few non-departmental shows at UA (which is how I met #1; she was a theatre major). But I hadn’t acted in three years, and I wasn’t Equity or anything (I am now). But I did play guitar and the viola. So, I went into the audition with Bartók’s Romanian Folk Dances and “Magic To Do” in my binder. They cast me in the ensemble. Fabulous show. And that’s how I met Margaret Hall—now CapRep’s Assistant Artistic Director—who was then directing their On-The-Go shows, educational theatre productions that toured schools all over the state. Two and a half weeks of rehearsal, then a month of performances, usually two a day, including travel, set-up, and breakdown. Hard work. Lots of fun. Margaret and I quickly became friends outside of the theatre, even if Theatre is what has most closely connected us. I would go on to appear in five of these tours, and even co-wrote the music and lyrics for one (a modern adaptation of “The Legend Of Sleepy Hollow”). I trust Margaret. She’s pretty no-nonsense about her visions for these shows. And, like Dr. Newman, she's trusted me with the materials. Sure, they might be for schoolchildren, but it’s pretty intense work with lots of moving parts and little-to-none of the visibility as main stage shows can bring. Margaret has put in lots of good words for me over the years, and she wrote me letters of recommendation most years I applied to grad school. When I think about Margaret, I think about the many branches of the tree of circumstances that grew into this moment: transferring schools>dating #1>Charlie>auditioning for Secret Garden>Margaret. And while I’m not one who puts a lot of stock in serendipity, it is worth appreciating this domino effect in our lives. Sure, the tree first sprouts by just being born if you go back far enough, but stopping well before that does lend a kind of mystery that’s perhaps needed so as not to feel so nihilistic about life.

Sleepy Hollow, Capital Repertory Theatre’s On-The-Go Production, Fall 2015

Directed by Margaret Hall

Book by Maggie Mancinelli Cahill, Music and Lyrics by Justin Friello and Lecco Morris

Left to right: Lecco Morris, Kristyn Youngblood, Justin Friello

***

All this work I did with CapRep really focused my attention on Theatre again, and I began to look at it not as an entity separate from music, but as something that could encompass and frame the music I was writing. Now, it’s true that Theatre had always been a medium for which I was interested in writing. That was the whole reason I moved with #1 to NYC in the first place: I was accepted into the BMI Musical Theatre Writing Workshop (and later moved on to the Advanced Workshop). I met Cleo Handler there, and we started writing our original musical, From The Fire, as our 2nd-year project. (Ten years and 3 readings later, we’ve got a fully orchestrated version of the show ready for any regional theatre or college theatre department that wants to stage it. [If you’re reading this and you hold any sway anywhere, please do our show. It’s so good, I promise, and I just know you’re never gonna come across another acoustic guitar-based show orchestrated with a female chorus AND a melodica featured so prominently.]) It felt like I was starting to find my people, though, at CapRep, and for the most part, they were working behind the scenes. One of these people—another bud at the end of those tree branches—was Matt Winning. Matt was the assistant director on CapRep’s 2017 production of Camelot, another show in which I was actor-musicianing. Now that I think about it, I don’t actually remember how we became friends. I don’t recall Matt playing a very front-facing role in that show. I know I saw him in rehearsals, but maybe it wasn’t my scenes he was directing. Anyway, somehow, Matt and I ended up as friends, and we spent a lot of time talking about the mechanics of Theatre, dissecting why certain productions we’d seen either worked or failed (usually the latter; we’re both grumpy). Matt was one of the few people who’d seen the last From The Fire reading, and he gave us really insightful notes, mostly about the degree to which the various devices used in the show were successful. (Margaret also saw this reading and gave equally helpful advice.) All these conversations with Matt started to point me toward this idea that the best kind of Theatre is exposed to some degree. That’s to say, tricking the audience into believing the action on stage is real doesn’t do anything to further whatever point you’re trying to get across. In fact, it probably does the opposite. (This idea is the basis for Brecht’s Epic Theatre, if you wanna get technical. Not that we ever discussed Brecht by name, and not that I ever studied Brecht [Matt did, he’s got a Master’s in Directing], but we sort of came to that conclusion just by analyzing our own engagement with Theatre and Pop Culture.) I took that idea to heart, and it would play a major role in my 2022 grad school applications.

Matt Winning, in my apartment, recording a pilot episode of a podcast I still wanna put out (it’s my fault; I never edited it), June 2022

***

The two years I spent at SUNY Purchase from 2007-2009 were two of the worst years of my life. I lost close to 15 pounds in my first semester; I lost three of my best friends from high school, one of which also went to Purchase (AWK-ward…); and I was struggling to write any music that felt original. I distinctly remember a confrontation in Comp Seminar (all the composition students met once a week for 90 minutes) when another student 2 years ahead of me said that I did not “write” the graphic score I had performed on a departmental recital, basically calling the idea of a graphic score bullshit. (That same student would go on to present a “score” consisting entirely of two pictures of celebrities, I want to say Jim Carrey and someone else, but I can’t remember. And had I then the confidence or the mental wherewithal, I would have thrown his own argument back in his face, but I was barely sleeping that semester, so a heated engagement was out of the question.) The only time I socialized outside of class was in the co-ed cappella group, Choral Pleasure, an ensemble I’d auditioned for my first semester. One of the people who ran Choral Pleasure was Andrew Fox, a junior (I think). Enthusiastic doesn’t come close to describing the energy this kid had (still has, really). He was from L.A., and he was a brilliant music writer, arranger, and orchestrator. He was also more than a few years older than me. He and I got into a lot of fights, the fun kind though, the brotherly kind, the kind where we both respected the hell out of each other but held diametrically opposing views on most everything about music. We antagonized each other every chance we got. But we both knew that the music the other one was writing was so different from everything else going on in that school (his words, I promise). Choral Pleasure was one of the few things (maybe the only thing) I missed after leaving Purchase.

Now that I think about it, one of two reasons I decided to go to Purchase was that four of my high school friends were going there. I was scared to go to college, not of the school part, the moving away. Having old friends in a new place was enticing. I should have gone to Ithaca College, but I didn’t. I only regret that choice on an academic level though, because, looking at that tree again, maybe none of this would have happened, and I wouldn’t have had nearly as rich of a musical life as I’ve had if I’d spent 4 years in Ithaca (a town, in what I’m choosing to view as some sort of sign, where, 5 years after finishing my undergrad, I would meet #2).

In the spring of 2012, I was living with #1 back in Schenectady. Now a year out from understand, I had the idea to apply to grad school. My senior year at UA, I’d written a musical adaptation of Michael Cunningham’s The Hours. (Don’t get me started on the recent opera, I’m mad they beat me to it.) I was really proud of the work; it was unlike anything I’d written before, and everyone I showed it to had really emotional responses to it. So I applied to NYU’s Musical Theatre Writing Program, got invited to participate in their 2-day in-person writing session (the last step in the audition process), and was accepted to the program. But I ended up declining because I was offered nearly no financial aid, and I couldn’t swing moving to the city; I was broke in Schenectady as it was. I reached out to Andrew for some advice. He said he was living in New York City now and was a composer of the BMI Musical Theatre Writing Workshop, a free program that met once a week, where people like Robert Lopez, Jeanine Tesori, and Alan Menken had gotten their starts, and that I should apply too. I was accepted to the program that summer, and #1 and I moved to New York the following November after nearly three months of me commuting to the city once a week to attend the Workshop. Though we never wrote anything together in BMI, Andrew and I would work on several projects together in New York and afterwards, most recently a music video series in honor of Stephen Sondheim’s birthday/death in which well-known Sondheim numbers are performed in wildly varying and unexpected genres. I worked on two videos for the project: “Lesson #8” in the style of DMB and “Another Hundred People” in the style of Sufjan Stevens’ “Chicago”. Of course, those videos would lead to Dr. Newman extending the invitation for me to speak at UA, which in turn made me feel a little more confident about having to TA and teach classes in grad school, and it was a teaching credit that was sorely missing from my CV. (Look up. There’s that tree again.) By the time I was applying to grad school in 2022, I’d already reached out to Nancy, Margaret, and Matt for rec letters. But that October, Andrew and the band he was playing in (led by Samantha Joy Pearlman) had traveled up from New York to Albany so we could play a double bill together at The Jive Hive. Another branch on the tree: Andrew recommended Sam as a vocal coach earlier that year, after I’d lost my voice for 3 months in another bout of asthmatic bronchitis. So Sam asked me to play the show together, they came up, and we had an incredible night, putting on an even more incredible show. A few weeks later, still reeling from the high of that event, and remembering just how important Andrew had been to my career, I asked him to write a letter of recommendation, and he obliged.

Andrew Fox and I, performing my song “History Lesson, Pt. 2” at the Jive Hive, Albany, NY, October 2022

***

On the June 12, 2022 episode of the podcast No Stupid Questions, “Should Toilets Be Free”, hosts Stephen Dubner (co-author of Freakonomics) and Angela Duckworth (author and professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania) talk about a Behavioral Economics study conducted in Israel which examined the behavior of parents when their daycares started charging them fees for arriving late to pick up their children. Stephen and Angela summarize the study in this way:

DUBNER: In Israel, these child daycare centers were having a hard time with parents picking up their kids late. So, they decided to institute a fine of, I think it was roughly three dollars American per late pickup. And once that happened, the share of late pickups went not down, but up.

DUCKWORTH: A lot!

DUBNER: Because the parents could just say, “Well, you know, now they’re just charging me for something that I want anyway, and I’ll pay three dollars, and it just gets added onto the bill.”

DUCKWORTH: They were like, “Wow, that is an awesome rate for childcare. Yes, please!”

DUBNER: So, again, when you change the price of something, when you change the incentives, behavior changes.

Reader, I don’t know why, but this hit me like an anvil. I was crushed, Wile E. Coyote style, but I couldn’t figure out why. I looked up the study, “A Fine Is A Price”, and read it in full (it’s quite short, only 18 pages). And reader, I was forever changed.

I’ve had lots of unsuccessful relationships (“It’s me, hi”). There’s plenty of reasons why so many of my songs are about heartache. But “A Fine Is A Price” made me think about my own behavior in a way that no therapist had been able to get me to do, and there’ve been a lot of therapists. This idea that when we are willing to pay a price (the fine; and in this case, an emotional price) in exchange for engaging in a certain behavior, or at least when we view this price as minimal, or perhaps we aren’t able to fully comprehend this price, then the behavior will continue regardless of how many times this fine is paid. Only when we account for the total sum of the fines paid over a lifetime can we begin to change our behavior.

I knew I had to write a piece about this.

***

In November of 2022, I took a trip to Houston, TX for my birthday, a dream destination for over a decade. I wanted go to Houston because that’s where Rothko Chapel is. Rothko Chapel, of course, is the one room nondenominational/interfaith spiritual space, lined with 14 floor-to-ceiling paintings by Mark Rothko, my favorite painter. Before I loved Rothko, I loved Morton Feldman, the composer, and my second favorite piece of his is Rothko Chapel, a work dedicated to the artist one year after the opening of the Chapel and two years after the artist’s death by suicide.

Rothko Chapel, Houston, TX

Image Credit: James Florio

So for my 33rd birthday, I flew myself down to Houston, and on the second day of the trip I visited the Chapel. It may have been frowned upon in what is an all-the-time silent space (the docents are very vigilant), but I had my earbuds in and listened to Rothko Chapel while walking around the space for the first time. But it wasn’t quite the experience I anticipated. I thought I’d feel something more; I think the build-up to and expectations for the moment stifled the moment itself. It wasn’t until the second and third visits (I was only there for 5 days) that the energy of the space became all-consuming. In the subsequent visits, without headphones, I found became more present, more capable of being subsumed by the energy of the room and self-insistence of Rothko’s work. I hesitate to call this a spiritual experience because I don’t know what that means. What most people call spiritual, I experience as emotionally overwhelming, and that’s as close to God as I think I’ll ever be: in that silent room, thinking not only about the last 15 years of wanting to be there, but everything that had happened to get me there: Purchase, UA, #1, NYC, Schenectady, CapRep, #2, the pandemic, and all the music-making in between. But this was not, ultimately, the revelation that I believe got me into grad school. That would take place a mile and a half south of the Chapel.

***

I was already doing something stupid applying to grad school for the fourth time. I was 32 at that point. At least the first time, at 26, I could see myself finishing up a PhD program by my 30s. But now I was looking ahead to 40, and looking ahead to anything during the third year of a global pandemic felt silly. (By that metric, the 2020 applications were the silliest of all. But I’m glad I didn’t get in then. Online learning sucks for the most part, and forget trying to make music—I was fed up with putting on livestreams after 9 months.) I’d had a FaceTime, however, with my cousin Josh (who’s pursuing his doctorate in classical saxophone performance at the University of Maryland), in early September 2022, when I applying for a fourth time wasn’t even a thought in my mind. We were talking about my job as a chef at a new café that I’d only had for a year, and I was telling him about some staff changes that were making me question if I was going to stay or look for a new job, or if I could get promoted; everything was up in the air. And he said, you should just apply to the comp program here at Maryland, get in, and then you’re set. I dismissed the idea in the moment, but after we hung up—after midnight—I did look at the faculty at UMD…and decided they weren’t my cup of tea. But the seed was planted, and I started looking at other schools. Lots of schools…before narrowing it down to six: Eastman, UCIC, USC, Brandeis, CUBoulder, and Syracuse.

Anyone who’s applied to anything knows that applying to anything is terrible. Now imagine you’re applying to something but you haven’t had any formal experience in that thing in 13 years. That was me in the fall of 2022. Sure, I’ve worked in all kinds of music since Purchase: music and theatre and creative directing and event planning; but the only professional classical thing I’ve done between 2009 and then was performing and arranging music for my friend Aden Brooks’ first doctoral trombone recital in Miami (right before the pandemic, in fact; and actually, that experience was what made me apply in 2020: I remembered what it was like to be around musicians 24/7, and it was so exciting). Suffice it to say, I knew I had to go big. When you apply to music school as a composer, you submit your portfolio of recent works. Well, my most recent piece worthy of submitting—which, like almost every other piece in my portfolio, had gone un-performed (the best thing I had was a MIDI excerpt because it was the only section I could get MIDI to perform; the whole back half of the piece is indeterminate, and I don’t play piano, saxophone, or percussion, so I sure as hell couldn’t record it myself)—was from 2020. Every year after getting rejected, I’d tell myself: never again. But this time it really did feel like this was it. 32 years old, now or never. So I set out to write, notate, AND record a new piece for the applications.

***

If nothing else, my music—my singer-songwriter material, anyway—is known for two qualities: 1) Sadness, and 2) Being about romantic relationships. Usually 1 and 2 are the related. And that strategy of telling the truth about the ups and downs of my personal life has led to a fair amount of success, both creatively and professionally. My classical music (I don’t like the label “classical”, but it’s easier to just use it here), on the other hand, had been more…well…cold, highly structured, and not necessarily easy on the ears. When I started writing classical music in middle school, I was focused on rhythm and melody. That feels strange to say now. Like, isn’t most of music just rhythm and melody? But as I got into my junior and senior years of high school, I was listening to more and more music by—guess who—Cage, Glass, and Monk…and Feldman and Earle Brown and Steve Reich. This collection of composers steered me away from rhythm and melody, toward two other facets of music: indeterminacy and harmony. And thus began a 15-year long journey into exploring how much could be done by handing performers a lot of very specifically-notated music and telling them they could control much of how that music was presented. There were pieces like 2006’s String Quartet No. 9 (Spectrums), 2008’s Alphabet Music (that graphic score I got into the argument about; performed in combination with Thirteen and three-fourths Mesostics on John Cage), 2014’s Nature Variations, and 2018’s my eyes are fond of the east side. (my eyes… was the heart of the 2018 and 2020 applications. It’s a huge piece, over a dozen instruments, with text from the eponymous poem by E. E. Cummings [did I mention that in high school I came up with the goal to set every Cummings poem to music? I’m a few hundred in]). It’ll never get performed. But I was positive that this was the way to go. Still, I’d show my music to people, mostly non-music people and non-classical-music people, and they’d be impressed by it, I guess? But it didn’t really mean anything to them, you know? They appreciated it. And I suppose everyone wants to be appreciated. But more than that, I think everyone wants to be understood. And the truth is, no one really understood it on an emotional level, even if I explained the mechanics behind its construction. Now, there were people at Purchase who got it, including my first private teacher, Suzanne Farrin, who hung the enormous oversized score for String Quartet No. 9 in her office, waiting for me when I walked in for my first lesson of undergrad (as if my ego needed more inflating). Andrew got it. And my only two composition friends, Sean Harold and Charlie Punchatz, did too. But after I left Purchase, after I thought I’d left classical music altogether, the creative people in my life who I cared about, weren’t responding like I hoped. This music meant a lot to me. I was inventing all these methods of composition, all these new techniques to come up with pitch and rhythmic material. And I felt like I was amalgamating all the lessons I’d been taught by that core group of composers from the end of high school into something really fresh. 2018 Justin really believed that. 2020 Justin did too. 2022 Justin, post-“A Fine Is A Price” and post-Houston Justin realized that this mission of exploring sound itself was the same mission that all the composers I loved and hated had undertaken since the Second World War. It wasn’t fresh. And, frankly, I wasn’t that good at it.

***

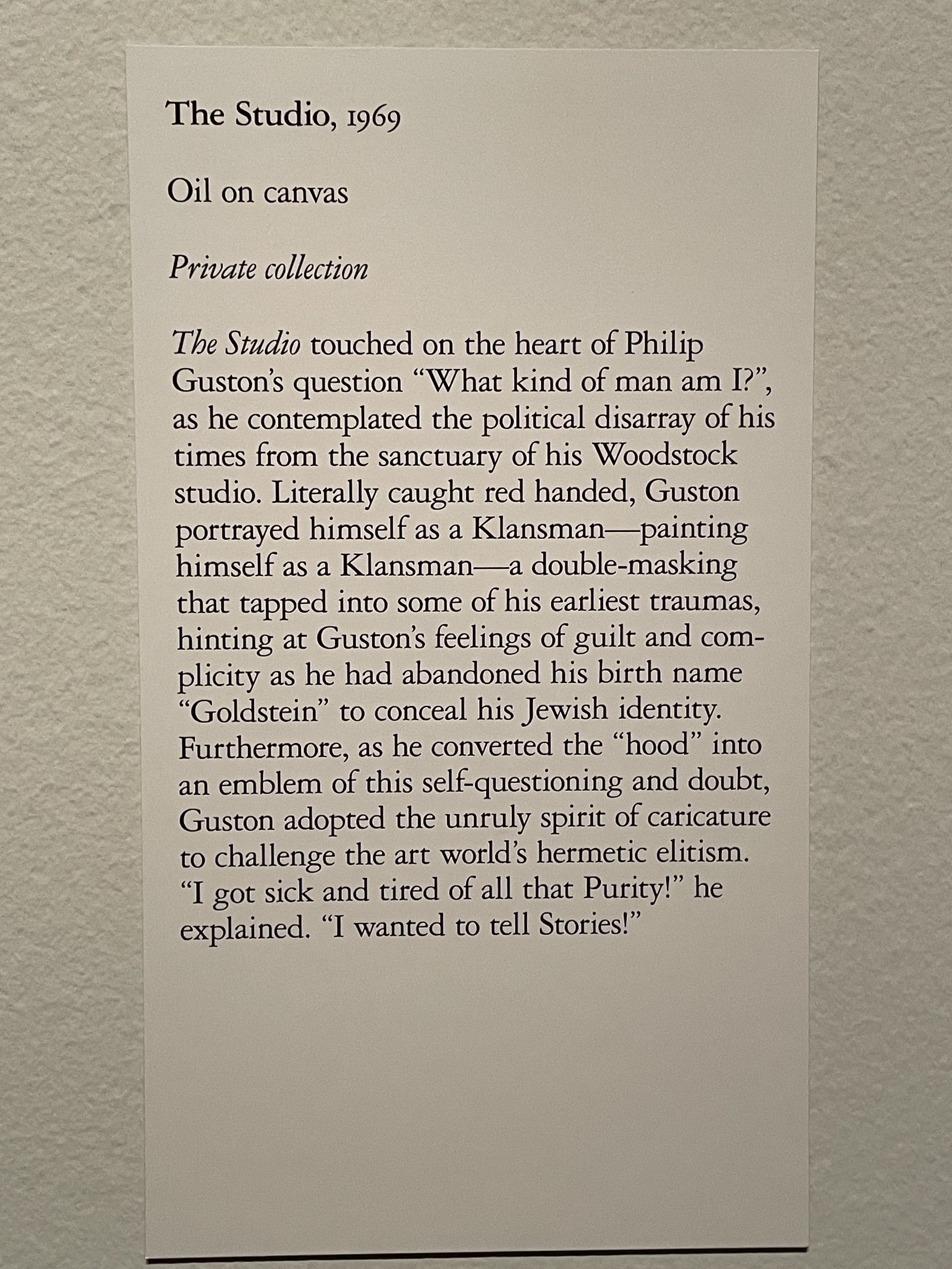

On my first night in Houston, before I even got to Rothko Chapel, I was falling asleep at my Airbnb, looking for things to do for the rest of the week when I read that the Houston MFA had a Philip Guston retrospective and was offering free admission that night only. Guston was a close friend of Feldman before they had a falling out over Guston’s shift from abstract to representational painting. I put on some pants and raced over to the museum. I knew Guston’s work a little, but I didn’t know it well. The exhibit stunned me. The physical scale of the works. The progression of his style: the sweeping change from realism to total abstraction, swinging back to what would be his signature cartoonish figures. It was incredibly moving. I left feeling invigorated, and a little pissed at Feldman for abandoning his friend! His late works were, to me, his most poignant and touching. But, hey, they were both geniuses. I went back to the exhibit twice more. On the final visit, on the penultimate day of my vacation, I stopped to read a title card that either I hadn’t read the previous two times or that I didn’t remember reading.

And that was it. The revelation I had been waiting for the entire trip. On the last day there. “I wanted to tell Stories!” I wanted to tell stories. I mean, Christ, I’d been telling stories my whole life in my songs. I was writing about my life in excruciating detail, in language I could not bring myself to use anywhere else in my life but somehow managed to wrangle into these exquisitely crafted musical selections. That was the material people connected with, that people cried over, that people told me moved and helped them. Why (excuse me) the fuck hadn’t I been doing that in my classical music? If human connection was the metric with which I was measuring musical success, I was so far off the mark in my classical work. Twenty years of firing the arrow past the target. Twenty years.

***

The total isolation of 2020 amplified my obsession with jigsaw puzzles, the culmination of which was a 3000-piece Where’s Waldo puzzle, and the reward for completing it was being able to search for Waldo and his friends (I’ve always had a crush on Wenda, Waldo’s girlfriend; lucky guy). Being nearly-unemployed (my hours were severely scaled back at the restaurant where I worked, even though there were only three of us left working there), I spent 6, 8, 10 hours a day working on this puzzle, and I was consuming more new music than ever before (thanks, Spotify playlist curators), needing a constant soundtrack to distract me from my worsening back pain from being hunched over the puzzling table so much. I wish I had a better lead up to this, just to make it more surprising, but I’d grown fond of Robert Ashley’s operas. A year or two before the pandemic, I became obsessed with Ashley’s Improvement, an opera that’s ostensibly about the breakdown of a marriage and the aftermath, but which is actually an allegory for the persecution of the Jews. I was driving to Ithaca, NY a lot, visiting #2, and Improvement was great driving music, allowing me to focus on not only the story, but the mechanics of his music. Improvement led to “Au Pair”, a section of Atalanta, and I couldn’t believe just how funny the libretto was. Let’s be real, comic operas are rarely truly funny, they don’t really touch our modern sense of humor. But “Au Pair” was about parenthood, adolescence, desire, race, and exploitation and crime. I never got tired of listening to those two works, and that remained true throughout the Waldo puzzle to this day.

The 3000-piece Where’s Waldo puzzle, completed January 18, 2021

I’m not sure what changed between 2007 and 2020. Maybe I just got older. Maybe I’d experienced real romance, real heartache. Built a life, only to have to turn down by my own hands. Maybe it was the fact that most of Ashley’s operas were written for spoken text, rather than singing, and, in conjunction with the extreme isolation of the pandemic, needing to feel spoken-to and engaged-with directly, rather than sung-at was more appealing. Maybe that’s what led to me turning the corner on Ashley’s music. Whatever the reason, the change came at the same time that I was realizing that my current compositional modus operandi wasn’t cutting it. And the characters in Ashley’s work all seemed to be simultaneously hopelessly entrenched in contentment and on the verge of psychosis.

In December 2021, I had a mental health episode that ended with a brief falling-out with someone who did not deserve to be on the other end of my actions. I hadn’t before experienced this level or duration of crisis, and it really scared me. It made me think about past episodes and their catalysts. Six months later, I read “A Fine Is A Price”. I went back to therapy. Patterns were discovered. And I couldn’t help but see connections between myself, the study, and Robert Ashley’s characters (my therapist, however, did not).

I was still in therapy after that early-fall conversation with Josh, having decided to apply to schools again, and I immediately set out to plan what would be my latest piece of music, A Fine Is A Price. I knew it had to be big. That study (and therapy) made me feel big emotions, and the scope of the piece had to match. I also knew that I had to draw on every aspect of my life and studies to make it happen. The piece had to be Theatre: Brechtian, exposed. It had to be autobiographical. It had to feature archival material. It had to use the text from the study, and that text had to be spoken; singing it would obscure the message. It had to use direct address. It had to be sad and ironic and silly. It had to use those compositional techniques I invented, but this time, put to use toward a different goal. Whereas for those twenty years I was trying to achieve, in the words of Philip Guston, a kind of musical purity, this piece had to be messy. Life is messy, so why shouldn’t music be too? It had to jump around from thought to thought, with little-to-no transitional material (not unlike this essay; that’s just how my brain works). It had to feel like the tree of circumstances that led to me writing the piece in the first place, featuring moments that shouldn’t be connected, and yet somehow they are by virtue of their having happened to me. It had to be a piece about itself, but it couldn’t be meta. It had to try to achieve too much. And it had to fail it. The piece alone could never capture all of how I felt, but it sure could try, and it had to be clear that I was trying. It had to be cryptic, about things I’ll never explain to people, moments in my life shared with partners that no one but them could possibly understand, put in this piece with the explicit expectation of audience confusion. In fact, the whole point of the piece was that you wouldn’t understand it, but that you sure would feel it. Ashley’s music pried out emotions I’d so deeply buried that the only choice I had was to use them as the foundation for the piece. It was the total opposite approach of anything else I’d done in my classical work. I didn’t care about writing a piece of music that showcased how smart or clever I was, and I didn’t care about the taste level of the piece, that is to say, I didn’t care about writing “good” music. My only intention was to create something that sounded like what it feels like to be me.

***

At 2am in my apartment, after the Jive Hive concert, I played Andrew a very rough demo version of A Fine Is A Price. It wasn’t mixed at all, and I only had half the score notated for him to follow along, but I wanted him to hear it, all 35 minutes of it. I didn’t tell him what the piece was about, but right after it ended, he starting telling me about his ex.

Bullseye.

***

I’d undertaken this giant task, not only to write and record the piece (I had to buy a MIDI keyboard to play all the parts I’d written, and I had to get a few female friends to come by my apartment to record the higher vocal lines in the middle, “operatic” section of the piece, including the person with whom I’d fallen out a year earlier (we made up a few months after), and I had to enlist my mother to record the opening section of the text because she, herself, was a preschool owner and teacher for nearly 40 years, but I had to notate the thing too. (Mind you, all of this was in the middle of getting promoted to head chef at work, suddenly working 45 or more hours a week alongside planning events.) And this was on top of writing all of the Statements of Purpose, organizing the rest of my portfolio, and filling out the endless online forms for seven schools. Right. Seven. A week before the seventh, unplanned school’s deadline, I had a phone conversation with a professor at another one of the schools I had already planned to apply to. This professor did not work in the composition department, and his phone number was given to me by Dr. Newman, who suggested he might have some good insights. Turns out he did, and his final piece of advice to me was to apply to the University of North Texas. Funny he should suggest that, as UNT was the only school that had previously advanced me to the interview stage. That was in 2020, and, having been rejected once, I didn’t consider it again. But on his advice, I quickly put together the required materials, and soon, I’d submitted all seven of my apps.

The cornerstone of the applications was A Fine Is A Price in tandem with my Personal Statement which began:

In the late 1960s, Philip Guston said, “I got sick and tired of all that Purity! I wanted to tell stories!” He was responding to criticism of his shift away from pure abstraction (which he found elitist and hermetic) in favor of a style that he felt more directly took on the socio-political issues of his time. It is with this spirit that I’m applying to Masters programs. In the last two decades, the world has become messy and overwhelming, and we need a messy and overwhelming art to accompany it. In composition, we can explore sound all we want, but no matter what we discover, new sounds are still just sounds (no longer new after their discovery), and not new conceptions of the medium. In recent years I have moved away from the purity of the sound-object in favor of storytelling, which is itself messy, subjective, and more complicated a subject because it centers humans, making it a) far more interesting to me, and b) the direction in which I believe contemporary composition should move.

It went on to say:

The majority of my pieces make heavy use of the Voice. Truthfully, I don't have much to say if there isn't text involved. Text setting is foundational to my work, as is—by extension—Theatre….As I mentioned above, I'm interested in narratives, particularly (auto)biographical ones. Furthermore, it matters little to me if the texts used in my pieces are understood on an intellectual level, although they often ask the audience to tune in more than they're perhaps used to. More important is that they be understood emotionally, even if the the question "What was that all about?" lingers. The goal with this kind of work is to combine the universal and commonplace with the personal, psychological, and emotional, resulting in the most intimate of moments being examined on a grand scale.

After returning from Houston, I rewrote all of my Statements of Purpose because I finally figured out exactly what my purpose was. And the piece I had spent two and a half months working on suddenly made sense too. If Improvement had used a personal narrative to allegorize a anthropological event, A Fine Is A Price did the inverse, using research on behavior to allegorize very personal choices. It wasn’t just a cathartic, sonic vomiting of ideas anymore; A Fine Is A Price became a manifesto, something that allowed me to make and back up a statement like “new sounds are still just sounds…and not new conceptions of the medium.”

In the interview with UNT, one of the professors said, “Regardless of what happens with this whole process, I want you to keep doing what you’re doing.” I felt validated, vindicated even. And when he later said, “You’re really trying to speak to the zeitgeist,” I felt like I wasn’t the one having to constantly explain my work in intellectual terms just so it could reach people. His statement was like someone had really studied what I was doing, just like I’d studied all those great composers in high school to get at the core of their work. And when, two months later, UNT put me on their waitlist, I was crushed because that felt like my only shot at getting in and studying with people who really understood me. And when, two months after that, and 5 days before the deadline when I had to choose between CUBoulder and Syracuse—having been accepted to those schools, knowing, however, that I’d have to spent more money than I wanted to to attend—the chair of UNT’s Composition department personally emailed me to tell me I’d been taken off the waitlist and was being given a scholarship which would qualify me for in-state tuition, and when, 2 weeks later, he again emailed to say that I was being offered a generous TA position in the Center for Experimental Music and Intermedia, I finally relaxed my body, accepting the offer, 6 years after getting the first itch to go back to school, finally accomplishing something that I never thought a 33-year-old, 12 years out of undergrad could ever do, forever changing the course of my career and life, and making me feel like all those years of trying finally paid off.

***

I began this essay with that Indigo Girls lyric not because I like that song. In fact, I hate that song. But it does raise a good point: there are things inside us that no amount of academia will ever successfully explain. And the thing about A Fine Is A Price is that I didn’t know that that was the motivation to write it until after I’d already written it. Using music to tell the world about my life has done more for my career than any amount of book learnin’. {*bites wheat stalk*} The irony, however, that I used this strategy to apply to grad school of all things is not lost on me.

***

I’m moving to Denton, Texas in early August. I’m really nervous, and I’m scared to give up my apartment, my job, and all the comforts I’ve accumulated over the last nine years; to move 1700 miles away from my friends and family; to start from scratch. But I’m excited too.

***

There will be a farewell concert. I’ll announce that soon. And it’ll be recorded on audio and video for everyone who can’t make it.

***

Shamelessly, I’m also accepting donations to help with the move. My venmo is @jfriello (just put “moving fund” in the description so I can allocate it properly).

***

Thank you for your support all these years. This journey would not be possible with you.

***

And here’s A Fine Is A Price: